|

This was the toughest day of the trip. We learned a great deal about the history of the Jewish presence in Kraków, and visited the concentration camps at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

And off we go to learn about the Holocaust.

This was a Jewish neighborhood when Jews lived here, but they don't anymore, because they were murdered.

Lanina explains.

The map shows the old Jewish Quarter.

That synagogue had to be built in a sunken area because it was illegal for a synagogue to be as high as a church.

Janina again pointed out that the old quarter no longer has any Jews living in it. All the restaurants that serve Jewish cuisine are owned and operated by goyim. See the green house? That’s where Helena Rubinstein was born.

“Place of meditation upon the martyrdom of 65,000 Polish citizens of Jewish nationality from Kraków and its environs killed by the Nazis during World War II.” See all the stones? It’s a custom to place them on Jewish graves as a sign of respect.

Let’s go visit a synagogue that has been restored in the years since the Nazis used it for their own purposes.

The plaques honor those who have contributed to restoring the synagogue.

It is being used for worship once again.

The lovely decorations have been restored.

Janina tells us all about it.

While inside, men must keep their heads covered.

The Nazis razed this old cemetery which dates from between the 16th and 19th centuries, and used it as a garbage dump.

After the war it was impossible to restore the cemetery to its previous condition, so all those headstones, many of which had been carted away by locals to use as garden decorations and such, were returned to the synagogue by those who had stolen them. People were allowed to drop them off in the dead of night, no questions asked. But lacking a detailed burial site map, the headstones were placed without regard for where bodies were actually buried. Janina said that there still are graves under this pathway.

One of the most common Jewish cemetery customs is to leave a small stone at the grave of a loved one after saying Kaddish or visiting. Its origins are rooted in ancient times and throughout the centuries the tradition of leaving a visitation stone has become part of the act of remembrance. The origin of this custom began long ago, when the deceased was not placed in a casket, but rather the body was prepared, washed, and wrapped in a burial shroud, or for a male, in his tallis (prayer shawl). Then the body would be placed in the ground, covered with dirt and then large stones would be placed atop the gravesite, preventing wild animals from digging up the remains. Over time, individuals would go back to the gravesite and continue to place stones, ensuring the security of the site and as a way to build up the “memory” of the loved one. As time passed on, and carved monuments became the preferred memorial, the custom of leaving a visitation stone became a symbolic gesture–a way for the visitor to say to the loved one, “I remember you…..”.

A very important rabbi is buried here. Note all the rocks.

It was a lovely day for learning about horrible events.

The guy I am chatting with, Jan Karski, a World War II Polish resistance movement leader, and later a professor at Georgetown University, came to the United States during World War II with documentation that convinced Roosevelt’s administration that atrocities were taking place in German concentration camps. Apparently there’s a bench just like this in Washington DC, but I have to admit I don’t remember ever having seen it.

This is a Jewish cultural center.

Janina comes here to take classes.

That's an old church.

Steven Spielberg shot some of Schindler’s List in the area beyond that doorway.

That area.

Have you ever seen Schindler‘s list? Remember the little girl with the red coat in a black-and-white movie? That scene was shot here.

This is what it was really like.

Now it's mostly deserted and covered in graffiti.

Mmmm street food.

Wish we had time to tarry in this outdoor market.

But we need to rush through

Because we have a bus ride ahead of us. We're going to the Nazi death camp, Auschwitz.

The countryside along the way is lovely.

On the drive to Auschwitz we discovered the rape fields are blooming now.

Nice homes and businesses.

That's a church over there.

After our bus driver did a remarkable job of backing our bus up a narrow country lane, we had lunch here.

All we got out of the deal was a small salad and a bowl of broccoli soup. It was fine, but not the best road scholar meal I have ever had.

Now we have arrived at Auschwitz. We're passing through security.

This is our guide, Monica.

All the prisoners at Auschwitz entered through this gate.

Arbeit Macht Frei, or “Work makes you free.” That was a lie of course, as nothing good made you free at Auschwitz.

No one knows exactly how many people were sent to Auschwitz, or how many died there. However, historians estimate that between 1940 and 1945, the Nazis sent at least 1.3 million people to Auschwitz. About 1.1 million of these people died or were killed at Auschwitz. Wikipedia.

It's a forbidding place, even today.

The visitors' tour of the main Auschwitz camp begins in Block 15, shown in the photo above, which houses an exhibit entitled Historical Introduction. The building is located at the corner of the first intersection of camp streets after you pass the camp kitchen near the "Arbeit Macht Frei" gate, which is behind the camera on the left. Organized groups begin their tour of the museum buildings here

We went into several of the buildings and saw horrible things.

Our headphones allow us to hear our guide.

She was matter-of-fact in her descriptions of atrocities.

This is where those who were to be worked to death were separated from those who were to die immediately.

These cans contained the poison pellets which became zyklon gas.

Barbed wire fences and watchtowers.

We saw bales of human hair, mountains of shoes and luggage, bushel baskets full of eyeglasses, just heartbreaking stuff.

Some slept on the floor in pallets.

While others slept on straw.

Toilets.

Washbasins.

Hall after hall of photos of the murdered.

This street seems appropriately desolate and ghostly.

They’ve done a good job of restoration here. It is compulsory for all Polish students to tour Auschwitz. Same for German students. The place is crawling with tourists, but they aren’t having a good time as tourists usually do. There were lots of sober faces.

Guard tower.

Prisoners were tortured by hanging from these posts.

Another guard tower.

I did take some satisfaction in seeing this. It’s the scaffold where Rudolph Hess, the first commandant of Auschwitz, was hanged after the war for his crimes. From Wikipedia: The most notorious commandant of Auschwitz was Rudolph Höss. Upon his capture after the war, his trial lasted from 11 to 29 March 1947. Höss was sentenced to death by hanging on 2 April 1947. The sentence was carried out on 16 April next to the crematorium of the former Auschwitz I concentration camp. He was hanged on a short-drop gallows constructed specifically for that purpose, at the location of the camp's Gestapo. The message on the board that marks the site reads: This is where the camp Gestapo was located. Prisoners suspected of involvement in the camp's underground resistance movement or of preparing to escape were interrogated here. Many prisoners died as a result of being beaten or tortured. The first commandant of Auschwitz, SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Höss, who was tried and sentenced to death after the war by the Polish Supreme National Tribunal, was hanged here on 16 April 1947.

That's where the Hess family lived.

Now let's quickly walk through gas chambers and crematoria.

The prisoners were herded naked into here.

Then they were gassed.

Then their bodies were shoved into ovens and burned.

But the Nazis couldn’t kill people fast enough at Auschwitz, so they built another extermination camp about a mile away. This is Birkenau.

There was no escape.

Prisoners arrived by rail at this station.

The tracks led to that stand of trees just opposite. The gas chambers and ovens were nearby. If you arrived here, you never came back.

People arrived at their doom crammed into railroad cars like this.

In her always matter-of-fact tone Monica tells us about the horror.

Ruins of a death camp.

Apparently these buildings were kitchens where food actually was prepared for prisoners.

Not that it sustained them for long.

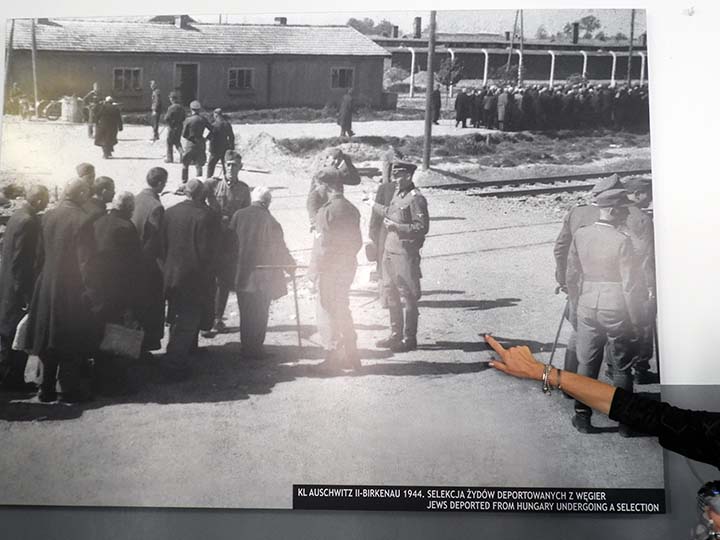

A scene from this spot long ago.

Totally sobered, we're headed back to the station.

Adjacent to it are some reconstructed barracks.

Toilets

Bunks. The cumulative effect of all this has been draining. It's time to head back to Krakow.

It was good to turn my mind to signs that look silly in Polish. Sure wish I had been quick enough to snap a shot of Motery Scootery.

Reconstruction of Krakow continues after the neglect of the Communist years.

Klezmer musicians from back in the day.

After the events of the day, how are we supposed to enjoy a nice dinner?

Some nice klezmer music should help.

Hey, the matzoh ball soup is delicious! Who knew?

|