|

Today we're going to learn how people lived on Crete 4,000 years ago. That's a long time.

But first, let's go on a walk in the early morning. Bill's still suffering jet lag and he's waking up long before he'd like.

So why not go back to that pretty fountain we saw last night?

It was built by the Venetians back when they ran things around here. It'll soon become obvious that lots of pretty things on Crete are left over from the Venetian period.

Things aren't as bustling this morning as they were last night.

There's our hotel: The Aquila Atlantis. Nice place on a steep hill.

And it's located near the docks.

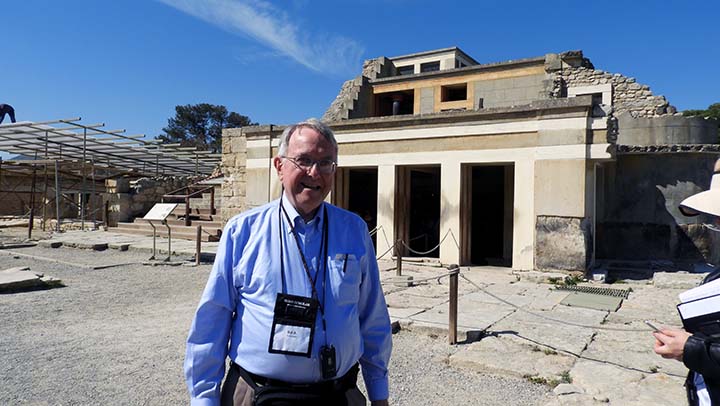

After a short bus ride we've arrived at Knossos. I'll bet you're wondering how they pronounce that, aren't you? Well, Bill was. He'd always thought the "K" was silent, and in fact for English speakers it is. But if you're Greek, it's kuh-NOSS-us. Or something close to that.

I'm pretty sure there's an archeological site up here somewhere.

Of course there is!

And Eleni is about to sit us down and tell us all about it.

Eleni explains it all.

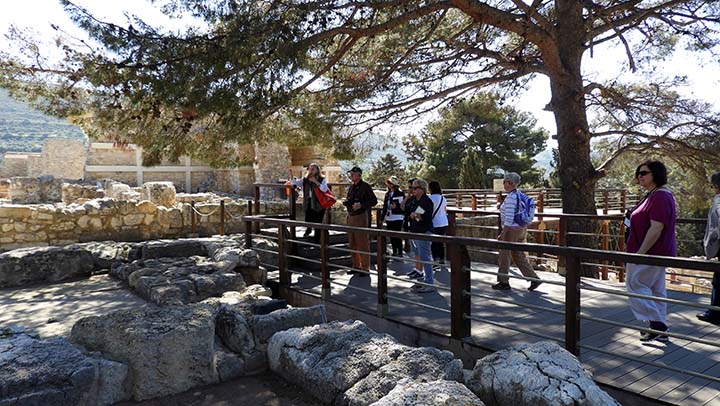

And the Road Scholars soak it all in.

Let's go walk the streets and alleyways of the ancient Minoans.

Knossos is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and has been called Europe's oldest city.

Settled as early as the Neolithic period, the name Knossos survives from ancient Greek references to the major city of Crete. The palace of Knossos eventually became the ceremonial and political centre of the Minoan civilization and culture. The palace was abandoned at some unknown time at the end of the Late Bronze Age, c. 1380–1100 BC. The reason why is unknown, but one of the many disasters that befell the palace is generally put forward. In the first palace period around 2000 BC the urban area reached a size of up to 18,000 people. In its peak the palace and surrounding city boasted a population of 100,000 people shortly after 1700 BC.

The site of Knossos has had a very long history of human habitation, beginning with the founding of the first Neolithic settlement c. 7000 BC. Neolithic remains are prolific in Crete. They are found in caves, rock shelters, houses and settlements. Knossos has a thick Neolithic layer indicating the site was a sequence of settlements before the Palace Period. The earliest was placed on bedrock. Arthur Evans, who unearthed the palace of Knossos in modern times, estimated that about 8000 BC a Neolithic people arrived at the hill, probably from overseas by boat, and placed the first of a succession of wattle and daub villages (modern radiocarbon dates have raised the estimate to 7000 – 6500 BC). Large numbers of clay and stone incised spools and whorls attest to local cloth-making. There are fine ground axe and mace heads of colored stone: greenstone, serpentine, diorite and jadeite, as well as obsidian knives and arrowheads along with the cores from which they were flaked. Most significant among the other small items were a large number of animal and human figurines, including nude sitting or standing females with exaggerated breasts and buttocks. Evans attributed them to the worship of the Neolithic mother goddess and figurines in general to religion.

Arthur Evans, who unearthed the palace of Knossos in modern times, estimated that about 8000 BC a Neolithic people arrived at the hill, probably from overseas by boat, and placed the first of a succession of wattle and daub villages (modern radiocarbon dates have raised the estimate to 7000 – 6500 BC). Large numbers of clay and stone incised spools and whorls attest to local cloth-making. There are fine ground axe and mace heads of colored stone: greenstone, serpentine, diorite and jadeite, as well as obsidian knives and arrowheads along with the cores from which they were flaked. Most significant among the other small items were a large number of animal and human figurines, including nude sitting or standing females with exaggerated breasts and buttocks. Evans attributed them to the worship of the Neolithic mother goddess and figurines in general to religion.

In many places throughout the ruins of the palace, attempts have been made in modern times to reconstruct what things looked like in antiquity.

So you tell me: is it a good thing to make an historically significant archeological site look like Disneyland? I suppose this was done with the best intentions, but I dunno...

The Minoans of 4,000 years ago really loved their bulls. Paul contemplates this representation of a bull's horns that he thinks maybe he remembers from when he was here in the early '60s at age 17. The fragment of the horn on the left is original; the rest is a modern reconstruction.

Much of the palace was wooden, so when the modern reconstruction was underway they gave the concrete a wood grain.

Grain was stored down there.

Eleni tells fascinating tales about what life was like back in the day.

The palace had a nice view.

Now we're going to see the actual royal throne of King Minos.

And there he sat, once upon a time. Well, that's what they say, anyhow. The throne room was unearthed in 1900 by British archaeologist Arthur Evans, during the first phase of his excavations in Knossos. It was found in the center of the palatial complex and west of the central court. This throne room is considered the oldest stone throne of the Aegean region, indeed the oldest in Europe. The chamber contains an alabaster seat on the north wall, identified by Evans as a "throne", while two Griffins rest on each side are staring at it. Moreover, on three sides it contains gypsum benches. It was part of a larger suite that also included an anteroom and an inner chamber with a ledge that was possibly a chapel. The throne room was accessed from the anteroom through two double doors. According to Evan's estimates, a total of thirty people could be accommodated both in the throne room and its anteroom. The room received its final form in Late Minoan IIIA period since it was a latter addition to the palace that occurred during the last phase of occupation after 1450 BC. Initially, Evans believed that this area was designed to serve a religious purpose, while he claimed that this was the priest-king's seat and that the presence of the griffins confirmed that this king was somehow beyond mortal realms. He also identified the stone throne as the seat of the mythical king of Crete, Minos, evidently applied Greek mythology. On the other hand, archaeologists Helga Reusch and Friedriech Matz suggested that the throne room was a sanctuary of a female divinity and that a priestess that sat there was her impersonator. The stone benches around the walls suggest a sitting council or perhaps a court, while a sunken area, called by Evans "lustral basin", partially partitioned off at one side, was used for ritual bathing. In view of the civil and religious powers held by the king, there can be little argument against the notion that proceedings of an official character began with sacred ceremonials.

According to various views, the throne itself may have actually had more religious than political significance, functioning in the re-enactment of epiphany rituals involving a High Priestess, as suggested by the iconography of griffins, palms, and altars in the wall-paintings. More recently, it has been suggested that the room was only used at dawn at certain times of the year for specific ceremonies.

I dunno, I guess maybe having the modern reconstructions here does help. Otherwise pretty much all we'd see would be rubble.

Bill, you really do need to lose that belly.

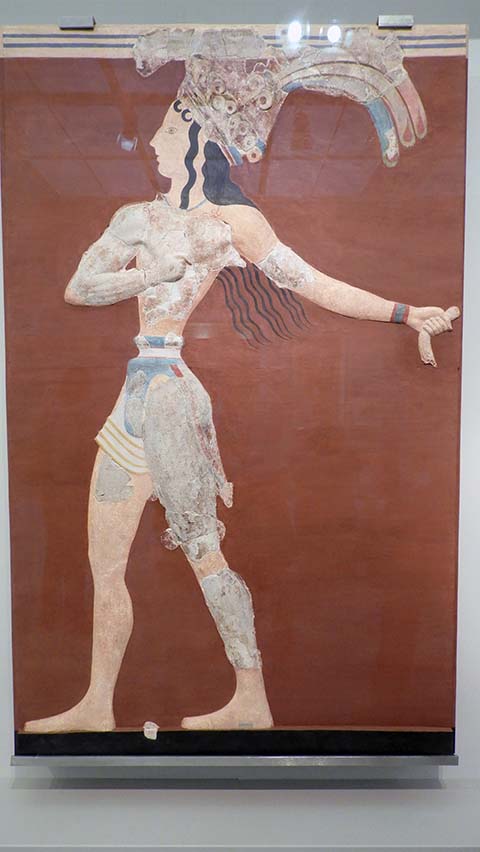

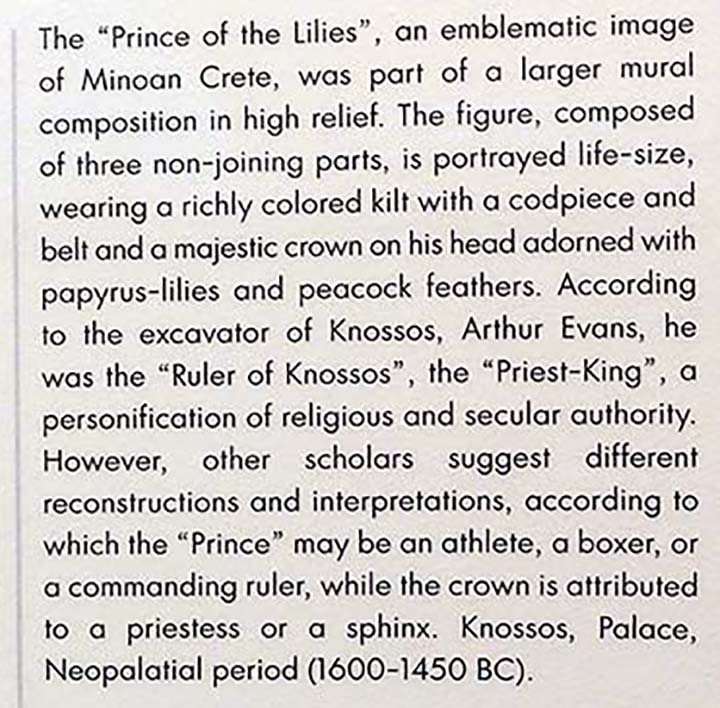

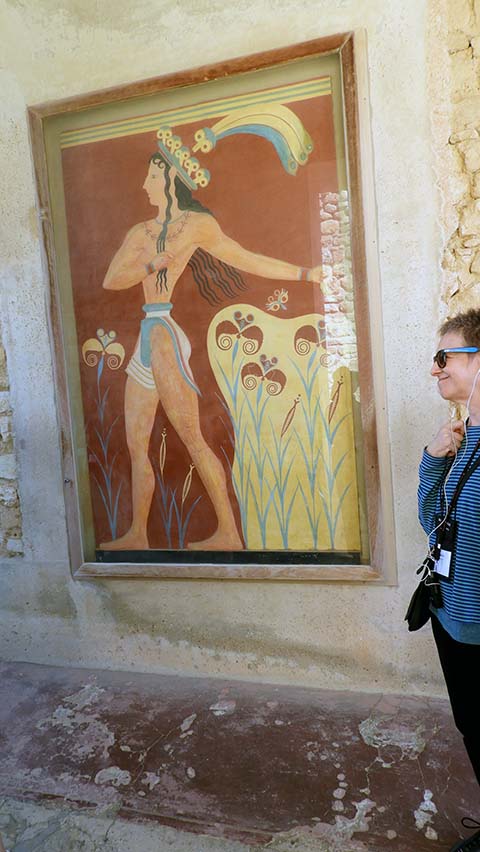

I mean, c'mon. You're never going to look as magnificent as the Prince of Lilies if you don't quit stuffing your face with Greek food. We'll see more of the Prince later, at the Archeological Museum. This is just a reproduction of the original fresco to give visitors an idea of what the wall decorations looked like long ago. This reproduction is placed at the Procession Fresco, a long passageway known as the Corridor of the Procession. It shows a young man strolling in a garden. He wears a short apron, which was incorrectly added by archaeologist Arthur Evans, a necklace of lilies, a crown of lilies and peacock feathers. He is thought to represent the Priest King of Knossos. Possibly he has a griffin or a sphinx on a leash in his left hand. His skin is painted white, which was normally reserved for depicting women.

There's a river down that hill. It was navigable back in the day.

Yes, I took a lot of pictures here, because the place was impressive. Leave me alone.

More reproduction.

Still more.

Over here, Road Scholars!

Eleni is still explaining it all.

You can store a lot of olive oil in pots like those.

Yeah, OK, I guess it's appropriate to have structures like this around to give visitors a sense of reference.

But I still prefer the real thing. Here's what was probably a sports arena. It looks like the perfect place for a little bull-jumping. Yep, as we'll see in a bit, Minoan daredevils just loved to flip over the heads of charging bulls and land on their backs. I know, I know, but just wait...you'll see.

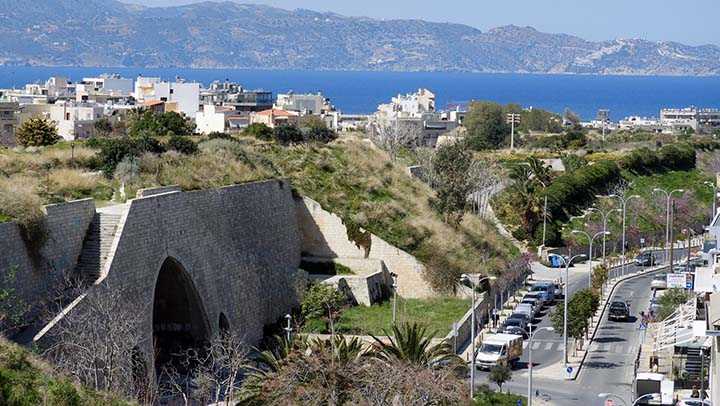

Heading back into Heraklion

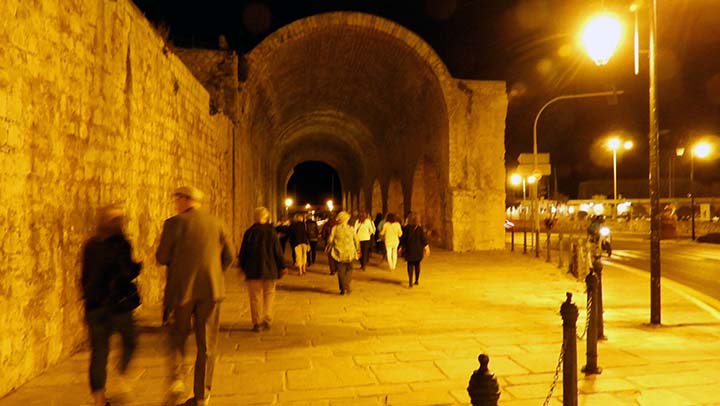

Here's part of what's left of the old Venetian wall around the city.

And there's the Gulf of Heraklion.

And that is, I do believe, Mt. Ida. Why do I keep remembering Charley Weaver?

Now before we go any further, let's climb a steep hill. If you can't climb a hill to see it in Greece, it's not worth seeing.

We've come up here to visit the grave of Nikos Kazantzakis (18 February 1883 – 26 October 1957), who is a famous Greek writer. Widely considered a giant of modern Greek literature, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in nine different years. Kazantzakis' novels included Zorba the Greek, Christ Recrucified (1948), Captain Michalis (1950), and The Last Temptation of Christ (1955). He also wrote plays, travel books, memoirs and philosophical essays such as The Saviors of God: Spiritual Exercises. His fame spread in the English-speaking world due to cinematic adaptations of Zorba the Greek (1964) and The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). He translated also a number of notable works into Modern Greek, such as the Divine Comedy, Thus Spoke Zarathustra and the Iliad.

Nick's gravesite has a nice view of Mt. Ida.

Well Bill's certainly impressed, anyway.

Look over there! It's the Face of Zeus! See it? Of course you see it! That's Juktas Mountain, and it was an important religious site for the Minoans.

More pretty views from the gravesite. There'd probably be a lot of people up here if they didn't have to hike up such a steep hill!

More Venetian wall. One of the books recommended for pre-trip reading by Road Scholar is called "Abducting a General: The Kreipe Operation and SOE in Crete." Bill read it prior to the trip and enjoyed it, but it wasn't until he got here and recognized that gate, which figured importantly in the abduction, that he really appreciated his advance preparation.

We're ready to enter the Archeological Museum of Heraklion.

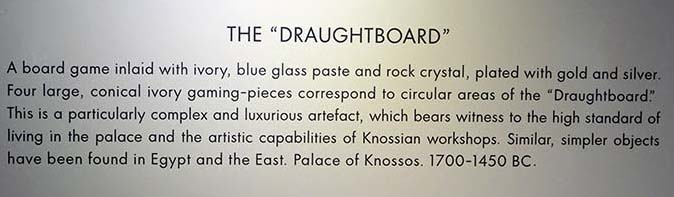

The poor Minoan kids didn't have Clue or Sorry or even Monopoly to pass the time, but they did have this.

I'd play it.

Here's a scale model of the Minoan palace at Knossos. There's a theory that the palace itself was the labyrinth of the Minotaur. It had been built upon so many times over so many years that visitors could find themselves lost inside its maze-like rooms. Well that's what they say.

One of the marvels of the Minoan culture is its art. That they could produce artifacts like this tells us they were a great civilization. You don't have time to spend making beautiful things if you have to be out in the woods all day trying to kill a rabbit for supper. Artists exist only when civilizations have grown to the point that citizens can develop specialized skills such as farming, teaching, healing, blacksmithing, and so forth. It's this division of labor that allows a few talented people to spend their time producing art.

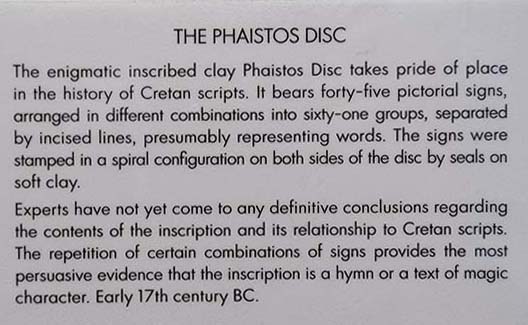

Nobody knows for sure what it says. But there are theories...

See? Nobody knows.

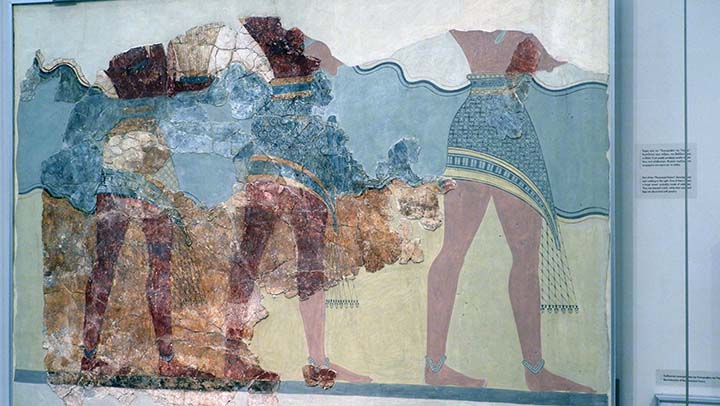

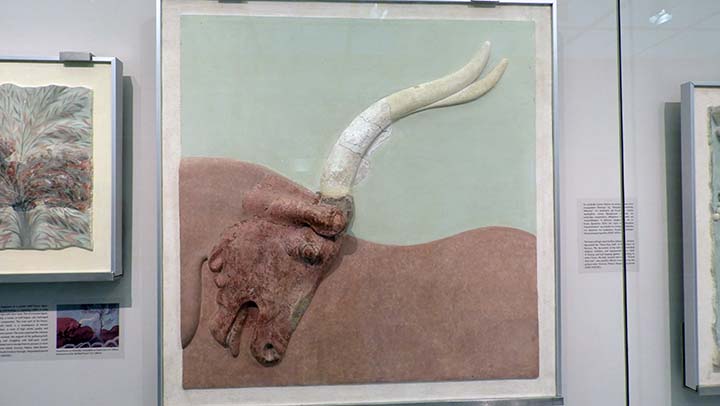

Now back to the subject of bull-jumping. Can you see what's going on in that fresco? The Bull-Leaping Fresco, as it has come to be called, is the most completely restored of several stucco panels originally sited on the upper-story portion of the east wall of the palace at Knossos in Crete. Although they were frescos, they were painted on stucco relief scenes and therefore are classified as plastic art. They were difficult to produce. The artist had to manage not only the altitude of the panel but also the simultaneous molding and painting of fresh stucco. The panels, therefore, do not represent the formative stages of the technique. In Minoan chronology, their polychrome hues – white, pale red, dark red, blue, black – exclude them from the Early Minoan (EM) and early Middle Minoan (MM) Periods. They are, in other words, instances of the "mature art" created no earlier than MM III. The flakes of the destroyed panels fell to the ground from the upper story during the destruction of the palace, probably by earthquake, in Late Minoan (LM) II. By that time the east stairwell, near which they fell, was disused, being partly ruinous. The theme is a stock scene, one of a few depicting the handling of bulls. Arthur Evans, Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, owner of the palace and director of excavation, presents the topic in Chapter III of his monumental work on Knossos and Minoan Civilization, Palace of Minos. There he calls the several frescos "The Taureador Frescos." And It was discovered in about 1917 Arthur Evans recognized that depictions of bulls and bull-handling had a long tradition represented by copious instances in multi-media art, not only at Knossos, and other sites on Crete, but also in the Aegean and on mainland Greece, with a tradition even more ancient in Egypt and the Middle East. At Knossos he distinguished between "bull-grappling scenes" or "'cow-boy' feats in the open" and "Circus Sports." The cowboy scenes depict the catching and handling of wild cattle, represented by animal icons very like the aurochs from which kine were domesticated. This type of cattle motif is shown on the stucco fresco in the North Entrance of the palace. Additionally, Jordan Wolfe, of Furman University, explains how the act of bull-leaping is especially significant to Minoan culture because it highlights man's dubious mastery of nature. The Circus Sports are to be contrasted to Bull-Catching. They are "a more structurally organized and ceremonial form of the sport confined, of its very nature, to a specially devised structure." He goes on to conjecture, "the Palace Bull-Ring itself lay on the river flat immediately below." The Taureador Frescoes, then, are not depictions of real events in real time, but are decorative motifs on the wall above a ceremonial bull-ring. They depict a stock scene, of a conventional nature, which has come to be termed "bull-leaping." It still has no viable definition. Although it vaguely brings to mind the act of jumping over bulls, the technique and the reasons for doing that remain obscure, a century after the discovery of the frescos. The frescos are no help. Modern attempts to recreate the leaping on modern cattle cowboys have resulted only in a number of deaths. In short, the bull is too fast, too powerful and too aggressive to allow seizure of the horns, much less the use of the energy of the neck toss for acrobatics. Moreover, that toss is a hook to the side, not a neat backward boost. The bull attempts to skewer the human with one horn, without a view toward the style of the frescos. It is possible to leap over small bulls without touching them, even as they charge, and such spectacles still practiced in France may be the ultimate source of the icon. A stationary bull might be touched or pushed on the way over, but pressing on a bull in motion would have the same effect as being sideswiped by a speeding vehicle; that is, tumbling out of control. The Taureador Frescoes are not frauds or incorrect reconstructions. The same bull-leaping scene appears in miniature in sealings and sealstones of the MM and LM periods. Explanations and classifications of the figures depicted are strictly theoretical, never illustrated by real-life examples. The only certain perception is that the leaper goes over the bull in an upside-down position, whether diving from above, leaping up from below, or with or without the assistance of another human or a device such as a pole. Why he should choose to do so also is strictly theoretical, although motives may probably presumed to be similar to those of modern adolescents in France: adventure and peer status. It would have to be, certainly, a volunteer activity of some social reward.

The bull-leaper, an ivory figurine from the palace of Knossos. The only complete surviving figure of a larger arrangement of figures. This is the earliest three dimensional representation of the bull leap. It is assumed that thin gold pins were used to suspend the figure over a bull.

Same figurine, different angle, different lighting. Graceful, isn't he?

The symbol of the labrys, or double-headed axe, was found frequently during archaeological excavations at the Bronze Age Palace of Knossos on the island of Crete, and has been referred to as one of the oldest symbols of Greek civilization. Solid gold representations of the labrys featuring Linear A inscriptions, upon which our gold Labrys jewellery is based, were found in a sanctuary in the cave of Arkalochori in Crete and are thought to date to before 1600 BC. Whilst the labrys continued to retain its practical use as a forestry and hewing tool in Minoan culture, it became imbued with a special religious significance from an early stage, which can also be seen in Thracian and mainland Greek art. For the Minoans on Crete, the symbol was especially associated with female divinities and priestesses and thus became a synonym for matriarchy. To find such an axe in the hands of a Minoan woman would therefore indicate that she held a powerful position within Minoan society.

Just look at the intricate carvings on this little Minoan vase.

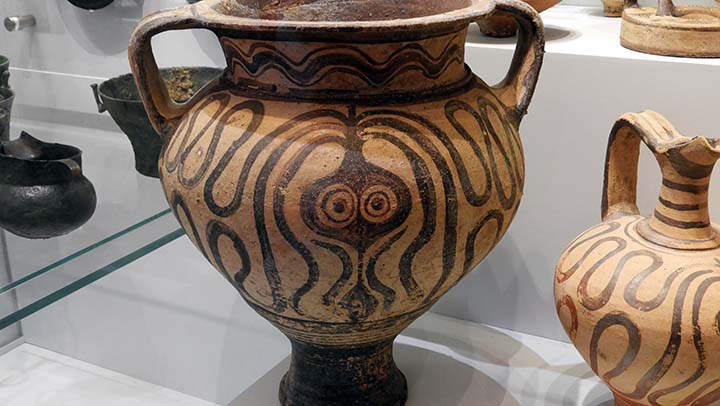

The Minoans did love their bulls.

These ladies represent the Minoan version of Mother Earth. The bared breasts symbolize life-giving nourishment and the snakes represent Earth. (They live so close to the ground they seem a part of it.)

More pretty fresco.

Minoan artists didn't just dabble in pots and frescoes -- they could produce some lovely jewelry too.

Eleni explains it all.

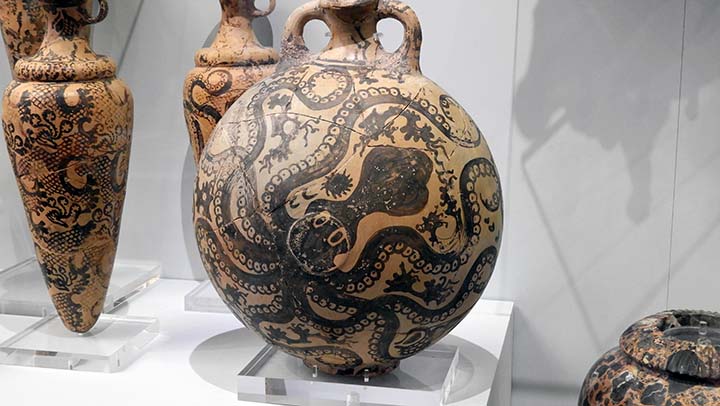

Now that is one surprised octopus.

Lovely and elaborate, it's amazing that this pottery has survived for millennia virtually unscathed.

This is a Minoan coffin, obviously designed for somebody important.

Bathtubs haven't changed all that much in 4,000 years.

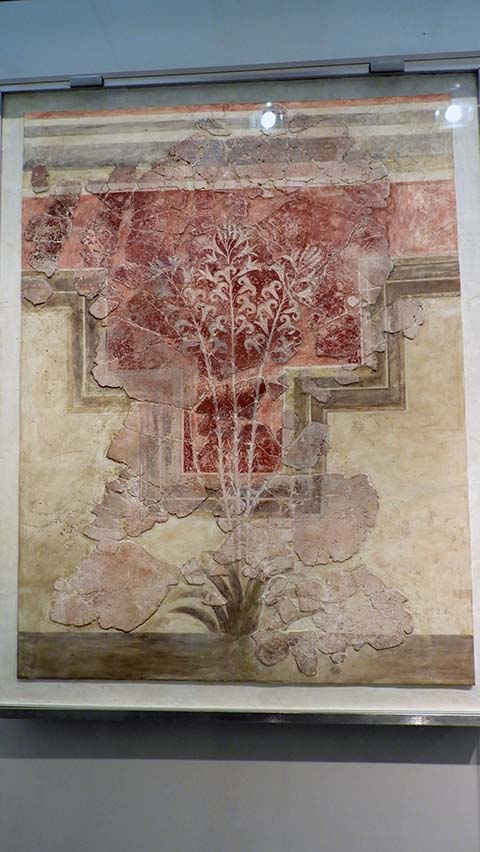

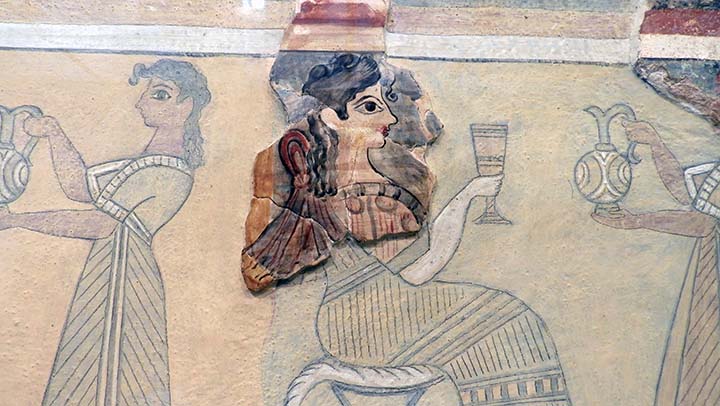

Fresco painting was one of the most important forms of Minoan art. Unfortunately, many of the surviving examples are fragmentary. The walls of the great halls of the palaces and houses of Crete were skillfully decorated with frescoes. The paint was applied swiftly while the wall plaster was still wet, so that the colors would be completely absorbed and would not fade. The Minoans followed the Egyptian convention regarding colors (e.g. red for men's flesh, white for women's flesh, yellow for gold, blue for silver, and red for bronze). Through the frescoes, one can gain the sense of the character of Minoan life and art and the Minoan joie de vivre. Some frescoes were reconstructed between 1450 and 1400 BC, when the Mycenaeans had established themselves on the island, and exhibit a completely different style of art.

Here are the fragments of the original Prince of Lilies fresco which were removed from the Palace and placed here in the museum. Anybody who wore a fancy hat like that was a certified big shot.

Told you.

Can you see how the fresco isn't flat, but raised from the plane of the wall?

More pretty fresco art.

Those Minoans really did like their bulls.

Two griffins giving each other some sort of signal, I think.

Still lovely after all these years.

A dolphin from 4,000 years ago.

OK, that's enough art for one day. Let's try a little Greek food culture.

This is just one of the things I appreciate so much about Road Scholar tours. We're not lunching in some tourist banquet hall -- we're sitting down with the locals to try some local fare.

Gyros! Eleni was very polite to call they JYE-roes because she knew that's what the Americans call them. But in Greece they're YEE-roes. And they're better in Greece than even in the good old USA.

Toby was a delightful traveling companion, as were her daughters.

Now that my friends, is a genuine Greek gyro sandwich.

Note the lack of tzatziki, that yogurt sauce on every gyro in America. If you want it in Greece, they certainly have it but you must ask for it.

Man these things were good. And the French fries were perfection. It's a late lunch, and very filling. Bill is stuffed.

So about three hours later, what do we do? We go out to dinner, that's what we do. That pretty fountain kept changing colors. Nice.

At least we get to walk to dinner with our bellies still full of gyro. That's more Venetian wall up ahead.

Surely this won't be a big dinner, right?

Dining with the locals again. Bill is so full he has vowed just to nibble anything put before him.

That's hummus over there. And Dolmathakia -- grape leaves stuffed with meat and rice. Just one, Bill.

Greek salad. Just a small taste.

Slices of zucchini, breaded and fried. Maybe just two. Mmmmm. OK, three.

Fried calamari. Just one. Nope, after a taste, just half of one.

Fried shrimp. Oh yes, oh my.....Three at least.

Anybody feeling full yet?

Full and happy. But no dessert, right?

Candied carrots. Candied orange peel. Nice. But those sweet slabs of semolina, halvas, were not Bill's favorite Greek food. And the stuff turned up in different sizes and shapes at practically every meal. Well, see, that's part of the fun of trying new foods!

Stop. Just stop. No more. Please.

Have I mentioned that's a pretty fountain? At least I know I'm on my way back to my room to rest my aching belly.

|

It

It is one of the greatest museums in Greece and the best in the world

for Minoan art, as it contains the most notable and complete

collection of artifacts of the Minoan civilization of Crete.

It

It is one of the greatest museums in Greece and the best in the world

for Minoan art, as it contains the most notable and complete

collection of artifacts of the Minoan civilization of Crete.