The Hart-Anderson Connection

In 1996 I used some of the information in "Joseph Hart and His

Descendants" to write the following as a 12th birthday present for my nieces. (Give

me a break--I took them to see "Les Miserables" too.) I tried to condense the

story so the girls could easily easily trace their ancestry back to the "Mr.

Hart" who emigrated with his wife to the New World in 1735.

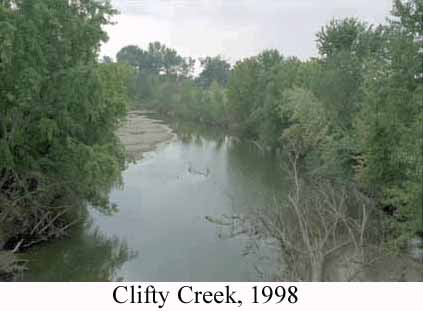

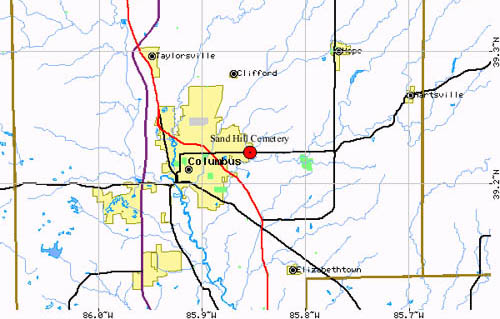

In October 1998 I happened to be driving near Columbus, Indiana, so I stopped to

take a few pictures. The terrain around Columbus is extremely flat, and the soil is so

rich that it's easy to understand why Joseph Hart and his family found the area attractive

for farming. I was somewhat surprised to find that the Sand Hill Graveyard was being well

maintained and that the headstones for Thomas & Elizabeth Hart and David & Nancy

Hart McAllie seemed to have been placed rather recently. Maybe someday I'll discover the

circumstances.

--Bill Anderson

Joseph Hart

About the year 1735, a Mr. Hart and his wife, both Scotch-Irish Presbyterians, departed

from Wales to emigrate to America. They left their native land because of persecution

directed against Presbyterians and Covenanters. They sought a home in the American

colonies so that they could worship God without molestation.

The voyage to America took more than four months, and during that time Mr. Hart died,

and his wife gave birth to a son whom she named Thomas. The widow and child landed at

Bordentown, New Jersey, where the mother brought up her son until he reached the age of

manhood. Nothing more is known about the mother.

The son, Thomas Hart, married a woman who had been married before (A widow? The book

doesn’t say). Her name was Mrs. Nancy Butler; her maiden name had been Nancy Stout;

and she had two brothers, John and St. Ledger Stout. All four of them moved together from

Bordentown, New Jersey to Loudon County, Virginia, where on June 16, 1761 Thomas and Nancy

had a son whom they named Joseph.

Joseph was his mother’s only child, and she died while he was an infant. After the

death of Joseph’s mother, his father placed him with a kind neighbor, and the boy

lived there until he was sixteen years old. When he was about ten or eleven years old, the

boy became a Christian, and his faith gave him great character which lasted throughout his

life.

In the meantime, Joseph’s father married again and he and his wife had three

children: Isaac, Alexander and Jane. Isaac became a farmer who married, lived and died in

Monroe County, Tennessee. Alexander moved to Georgia, where he became a successful cotton

planter and raised a large family that eventually scattered throughout the West and

Southwest. Jane remained close to her half-brother Joseph, and we’ll discuss her

story a little later.

In the early part of 1777, Joseph Hart’s foster father was drafted into the Army

of the Revolution from Loudon County, Virginia. In those days, men who were called to

serve could send substitutes, and Joseph volunteered to join the army in his foster

father’s place. He reasoned, "You have a family, and should you be killed, your

family will have no protector. You took care of me in my childhood; I will now be your

substitute in the army, for I have no one dependent on me."

The author of Joseph Hart and His Descendants, C.C. Hart, apparently sent a

request for information about Joseph Hart’s Army service to the Record and Pension

Office, War Department, in Washington, DC. In October 1895 he received a reply from F. C.

Ainsworth, Col. U.S. Army. The letter reported that Joseph Hart served in Captain

Holcomb’s company of the Fourth Virginia Regiment, commanded by Colonel Thomas

Elliot, and also in Captain Thomas Ridley’s company of the Virginia Regiment,

commanded by Colonel Robert Lawson, Revolutionary War. Joseph’s name first appears on

the rolls of the Fourth Virginia Regiment for April 1777, and it appears also on the

subsequent rolls until he is reported "Discharged, February 16, 1778." Neither

the date nor the term of his enlistment was shown by the record.

Soon after his enlistment in April 1777, Joseph’s regiment was ordered to South

Carolina. In the following September, Captain Holcomb’s company was engaged in a

moonlight battle with some British and Tories near Guilford Courthouse, South Carolina. In

this battle, many of the privates were either killed or wounded, and the muster roll of

the company was lost. It was after this battle that Joseph began serving in Captain

Ridley’s company, commanded by Colonel Lawson.

Joseph was wounded in the right hip by a musket ball. After the battle he was placed on

a horse and along with several other wounded soldiers he was taken to a barn two miles

away where he lay until morning. He wore buckskin breeches, and when the surgeon came to

examine him, he found the right leg of his this garment so stiff with blood that it could

not be removed until it was cut from top to bottom. The wound was so severe that Joseph

was found unfit for further military service. The ball had lodged deep in his groin and

was not removed; so for the rest of his life Joseph carried British lead in his body. His

condition meant that he was never afterward able to do a day’s hard labor, but still

he was very active, even up to old age.

After his discharge from the Army, Joseph returned home to Virginia. But Joseph

wasn’t happy in Loudon County, where slavery existed. Joseph’s Christian

principles had convinced him that slavery was a wrong to his fellow man and therefore a

sin against God. When he was nineteen years old, he left Loudon County, Virginia and moved

to Tygert’s Valley in Greene County, Virginia, where at the time, slavery was not

tolerated. But in Tygert’s Valley there was much fertile, unoccupied land which

attracted the attention of slave-holding tobacco planters. When the slave-holders moved

in, Joseph left the area, moving to Washington County, Virginia.

Here, in 1788 at the age of 27, he married a young lady named Nancy Shanklin, and their

first son was born in 1789. But then the slave-holding planters began moving into

Washington County, and Joseph started looking around for another place to live. In the

hope that the colony of Tennessee would enter the Union as a free state, he made a journey

to Blount County in East Tennessee. He liked the area, so in the spring of 1790 Joseph

took his wife and child and his half-sister Jane, and moved into the area that is now

Maryville, Tennessee.

The American frontier was a little rougher in Tennessee than it had been in Virginia.

Local Indians of the Cherokee and Creek tribes had been removed to Georgia, but sometimes

a few would return. They were known to steal horses and kill any white people who happened

to be around. To protect themselves, Joseph and other pioneer settlers (including a man

named Arthur Greer) built a blockhouse and fort--known as "Old Fort

McTeer"--part of which was still to be seen within the corporate limits of Maryville

as late as the year 1901.

The Harts lived in the fort for four or five years, and two of their children were born

there. During this time Joseph bought 320 acres, three and a half miles northeast of the

fort, where he cleared land and built the first two-story frame house in Blount County.

The house was located near the "Big Spring," and a part of it was standing in

the year 1900, still occupied by a member of the Hart family. Here Joseph planted an apple

orchard, and some of the trees were still bearing fruit a hundred years after the

planting. When it was considered safe from Indian raids, the family moved into their home

and lived there until 1821.

In 1797 Jane Hart married Arthur Greer in the house, and the two of them lived in

Blount County for the rest of their lives. They raised numerous children, many of whom

were still living in Blount and Knox Counties in 1900. C.C. Hart called them "a noble

race of Presbyterians of Scotch-Irish descent."

Though converted in early youth, Joseph Hart did not become publicly religious until

about the year 1796, when he and his wife joined New Providence Presbyterian Church. Soon

after joining, Joseph was made an elder in the church and Clerk of Session. He often

"set the tune" and led the singing in the church. Because the congregation had

few hymn books, Joseph would loudly read two lines of a hymn, lead the singing of the two

lines, and then read another two lines and sing and so on.

Tragedy struck in 1807 when, after a short illness, Joseph’s wife Nancy died,

leaving him with five sons and one daughter: Edward, born in Washington County, Virginia

1n 1789; Thomas, born in the fort in 1791 (This narrative will tell much more about Thomas

and his descendants.); Joseph, Jr., born in the fort in 1793; Silas, born in the farm home

in 1796; Gideon Blackburn, born on the farm in 1798; and Elizabeth, born on the farm in

1802.

In 1809 Joseph married again, this time to Miss Mary Means of Blount County, a maiden

lady 32 years of age. Her parents had left northern Ireland about the year 1780 to escape

religious persecution (they were Presbyterians), and settled in East Tennessee. Joseph and

Mary had five sons: William in 1810; Samuel in 1813; James Harvey in 1815; Isaac Anderson

in 1817 (died in infancy); and Charles Coffin in 1820. (Charles Coffin is the Rev. C. C.

Hart who wrote Joseph Hart and His Descendants. He was also known as "Uncle

Charlie.") All were born in the family home in Blount County. C. C. Hart marveled

that Joseph had ten sons and one daughter, and his son Thomas eventually had ten daughters

and one son.

Joseph Hart was quite an industrious man. He taught the first school in Blount County

at a schoolhouse about two miles from Maryville. He also owned the first four-horse team

known in the county. After the countryside began to be settled and there was no longer

danger from the Indians, Joseph became a "frontier truck driver." He used his

four-horse team to carry farm-raised vegetables and other produce into the gold mining

region of Georgia. There he would trade the food for cotton which he took to Baltimore,

Maryland. In Baltimore he traded the cotton for manufactured goods which he brought back

to the merchants of Maryville and Knoxville. The round trip took about three months.

Because of his war wound, Joseph wasn’t able to do any hard work on these trips, but

his older sons pitched in and helped. One of them said of his father, "He’s

always in the saddle."

In about 1818 while Joseph was having a vicious horse shod, the horse jumped on him,

injuring his right shoulder, so that he was never afterwards able to put on or take off

his coat without help. The horse belonged to his half-sister, Jane. Mostly, though, the

Harts were a healthy family. During the 26 years that they lived on the farm near

Maryville, a doctor was called only twice: once to see about Joseph’s shoulder and on

another occasion to see one of the boys who was suffering with "white swelling."

(I don’t know what that is, but it certainly sounds bad...BA)

Just as life was becoming comfortable for Joseph Hart and his family, Tennessee entered

the Union as a slave state. Still morally opposed to the institution of slavery, Joseph

decided to leave the South altogether. In the spring of 1820 he sent his son, Gideon

Blackburn Hart, west to find a suitable place for the family to settle. Gideon went to

Indiana, visiting Vincennes, Terre Haute and the central part of the state, and he finally

proposed Bartholomew County, Indiana as the future home of the family. About the middle of

September, 1821, the Harts were prepared for a momentous event: emigration to what was

effectively a new country. They had said good-bye to the old home, to old and familiar

scenes, to old neighbors, to the old church, and to a man who had become their dear

friend, Rev. Isaac Anderson. Neighbors and friends came to see them off. The traveling

company consisted of the father, the mother, Silas and Elizabeth of the first family, the

four boys of the second family, and Robert McClure, a young man hired for the occasion.

They were provided with two wagons, each with two horses, an extra horse with saddle

(which the father rode), a large tent, and two cows which furnished milk for the journey

and (later) at their new home.

The first evening the family pitched the tent by Will’s Creek, a whole seven miles

from where they started. (Cross country travel took more time in the days before

interstate highways...BA.) After eating supper and caring for the animals, the group read

the Bible and prayed and took their first night’s rest in the wilderness. The next

morning before daylight, William Trotter, a young farmer and a leader of the singing at

the New Providence Church, rode out to the camp on horseback accompanied by his brother.

William Trotter was engaged to be married to Elizabeth Hart, and he had promised to go to

Indiana the next spring to be married there. But it took only one night away from

Elizabeth for William to realize he could not bear to be away from her. He persuaded her

to return to Maryville to be married that morning. Silas Hart accompanied Elizabeth and

the Trotter brothers to the wedding (performed by Dr. Anderson), and the happy couple

rejoined the family at the next campsite. The group never traveled on the Sabbath, and the

entire journey to Indiana took about four weeks.

Gideon Blackburn was still in Indiana--around Vincennes--and when he learned that the

family was moving, he followed the military road opened by Gen. William Henry Harrison,

Governor of the Northwest Territory, from Vincennes to the Tobacco landing on the Ohio

River, near Leavenworth, Indiana. From there he went to Kentucky and met the family in the

region of the Cumberland Gap, and accompanied them to their destination, near Clifty

Creek, five miles east of Columbus, Bartholomew County, Indiana. The travelers arrived at

Clifty Creek on October 8, 1820. Gideon Blackburn was still in Indiana--around Vincennes--and when he learned that the

family was moving, he followed the military road opened by Gen. William Henry Harrison,

Governor of the Northwest Territory, from Vincennes to the Tobacco landing on the Ohio

River, near Leavenworth, Indiana. From there he went to Kentucky and met the family in the

region of the Cumberland Gap, and accompanied them to their destination, near Clifty

Creek, five miles east of Columbus, Bartholomew County, Indiana. The travelers arrived at

Clifty Creek on October 8, 1820.

In those days, when people were just beginning to move west, the government held claim

to much of the land and would not sell an individual less than 160

acres--one quarter section--on which to settle and build a farm. The price of the land was

$2 per acre. But for half the amount--$160--a settler could get a "certificate of

entry" and have five years to pay the remainder of the debt. In addition, no taxes

could be collected during those five years. At the end of the five years, when the rest of

the money was paid, the government would issue a deed (C. C. Hart used the word

"patent") for the land. Joseph chose his quarter section in Bartholomew County

and sent his son Gideon with $160 in silver to the land office at Jeffersonville, Indiana,

about 100 miles away. Gideon entered the land according to law.

Gideon, Silas and McClure cut the logs for a cabin, carved boards for the roof, and

split the puncheons for the floor. A neighbor, Mr. Elijah Sloan, used his team of oxen to

haul timbers to the building spot. The neighbors came together and built the cabin and put

the roof up in one day. The next day they laid the puncheon floor, built the chimney, put

the window and door in place, and by evening the family moved into their new western home.

The neighbors were very helpful; the cabin was built quickly and cost no money.

The cabin measured 16 x 18 feet, and had the common outdoor "mud and stick"

chimney, one window and one door. The window had nine 8 x 10 panes (C. C. Hart called them

"lights") and two sash. There was no sawed lumber except the sash and the window

frame, and these were brought from Tennessee. No nails were used except a few made by a

blacksmith in Tennessee and brought along on the trip. The nails were used in making the

door, the hinges and fastenings, which were formed of hickory. From the time of arrival

until moving into the cabin (about six weeks), the family lived in the tent and the

wagons. Silas, Gideon and McClure dug a well, built a stable, cleared and fenced twelve

acres of land and had it ready for planting by May 1, 1821. Silas and McClure remained

with the family for a year, and in early May 1822 they took one of the wagons and two

horses and returned to Blount County, Tennessee.

Deer, foxes, raccoons, opossums, squirrels, turkeys, quail, pheasant and other wild

game were plentiful in the forest surrounding the cabin. Occasionally the family also saw

wolves, bears and panthers lurking among the trees. The creeks and rivers abounded with

fish. Joseph, however, was opposed to hunting because he thought it encouraged an idle,

shiftless manner of life. He refused to have a gun in the house.

Every morning and evening in the cabin, the family participated in the reading of the

Bible, the singing of a hymn, and the offering of a prayer. When Joseph was away, his wife

Mary conducted the service.

There, in their cabin, by a blazing fire of beech and hickory in the winter evenings,

and in warm weather by the light made by the dry bark of the great poplar trees, Mary spun

flax on the "little wheel" or engaged in knitting, while Joseph and the boys

memorized Bible verses and the questions and answers of the Shorter Catechism. Afterward,

the boys would engage in simple play while Joseph would sing hymns from memory, such as

"How Firm a Foundation Ye Saints of the Lord," "When I can Read My Title

Clear," "There is a Fountain Filled With Blood," "Am I a Soldier of

the Cross" and many others. Once a week one of the boys would read aloud the Cincinnati

Journal, a newspaper, while everybody paid the strictest attention. Every other week

the family shelled a "grist" of corn (two and a half bushels) that was taken by

horseback the next day to be ground at a nearby mill.

Often traveling preachers would stop by for a visit, notably Rev. John M. Dickey, and

would examine the boys as to their knowledge of the catechism. Also, because the cabin was

the only preaching place in the neighborhood for several years, when a preacher arrived

the neighbors would be notified and they would all leave their work and come to the cabin

to hear a sermon.

The family’s food and clothing were very simple. Clothes were made almost only of

wool and flax; they had several sheep to supply wool, and they raised a "patch"

of flax every year. The wool and flax were spun, woven and made into garments at home or

by exchanging work with some neighbor. Joseph made the shoes for the family. Hats for

summer were made of rye straw or splits from buckeye trees. Their food consisted almost

entirely of cornbread, mush and milk, and vegetables, with a limited amount of pork, eggs,

chickens, fish and wild game caught in traps. Tea and coffee were almost unknown. They

raised some buckwheat and ground it in a corn mill. For the first five years they raised

very little wheat, because the area had no mill that could grind it into flour. There was

no fruit until seeds they had brought from the old home in Tennessee could grow into fruit

trees. Every spring the settlers made sugar from the sap of the sugar maple trees that

grew abundantly in the area.

The following note is from the history of Bartholomew County: "On the third day of

July, 1824, the Presbyterian church of Columbus was organized, consisting of seventeen

members. Joseph Hart and his wife, Mary Hart, are the first names on the roll. Mr. Hart

was made Ruling Elder, and for many years was the only Ruling Elder, and was Clerk of the

Session until the time of his death. Presbyterianism and Christianity in this community

owe a great deal to this godly man."

In those days whisky was cheap--18¾ cents per gallon--or six gallons for a dollar.

Whisky was customarily served at all neighborhood gatherings, such as log-rollings, house

or barn raisings, harvestings, corn huskings, and sometimes at weddings. Joseph, however,

was a tee-totaler and he would never allow liquor on his land. In the spring of 1825 a

half-day’s log rolling was to be held, and the neighbors were to be invited. Joseph

instructed one of his sons to deliver the invitation to all the neighbors and to be sure

to tell them, "There will be no whisky, but Father says he will try to treat you

well." All the neighbors came. About the middle of the afternoon Mary sent to the

field a pot of hot coffee, milk, sugar, tin cups and pewter spoons, along with a large

tray of corn pone. Joseph said, "Come men, let’s have some refreshments."

The men stopped their work, sat on logs and seemed truly to enjoy this substitute for

whisky. Later in the afternoon, just before sunset, everyone was called to supper, after

which they voted this the best log rolling of the season. Joseph’s example had a

remarkable effect on local area customs, for in a few years no whisky was seen at any

neighborhood gatherings.

Joseph served several years as a magistrate (judge). In those days the magistrates of

the county met twice each month and held County Court. Much of the judicial business of

the county was conducted at these meetings. Joseph served several years as a magistrate (judge). In those days the magistrates of

the county met twice each month and held County Court. Much of the judicial business of

the county was conducted at these meetings.

Joseph taught school in both winter and summer, but mostly in summer. The textbooks

used in these pioneer schools were "Noah Webster’s Elementary Spelling

Book," "Introduction to the English Reader," the New Testament and

"Pike’s" or "Smiley’s Arithmetic." The students varied in

age and all were taught in a single room. Group classes were conducted only in

spelling--other subjects were taught individually. Children who could spell words of only

one or two syllables were lined up and exercised in spelling from memory (or "for

head" as C. C. Hart called it) just before the noon recess. The more accomplished

spellers went through the same exercise in the afternoons. Reading students read to Joseph

one at a time, several lessons every day. Children studying arithmetic seldom did anything

else, except to practice spelling and writing. The students brought quills to Joseph and

he made them into the quill pens that were used for writing. In those days, some schools

were called "loud schools" because all the students were required to study

aloud. Joseph’s school was a VERY loud school!

In the spring of 1826 Joseph organized the first Sunday School (Sabbath School) in the

county. The exercises of this school consisted of reading the Scriptures, singing a hymn,

praying, and reciting verses of Scripture committed to memory during the week. Some

students recited 25 to 50 verses every Sunday.

Joseph engaged occasionally in work for the American Bible Society. In 1901 there were

still Bibles in Bartholomew County furnished by Joseph Hart.

Another tragedy struck Joseph and his family on the afternoon of June 6, 1826. Joseph

was teaching in the schoolhouse and his three younger boys were in school. Mrs. Sloan, a

neighbor, was spending the afternoon with Mary. A boy came to the schoolhouse and looking

in, exclaimed, "William is drowned!" Joseph’s son William was only 16 years

old. Joseph and two of his sons ran to the creek where the tragedy had occurred, half a

mile away, and the other son ran home to break the news to his mother who was preparing

dinner. In a whisper he told her what had happened, and Mary turned to Mrs. Sloan and

said, "My son is drowned!" Mary knelt by a chair and prayed, and after asking

what had happened, she continued with her work, prepared supper, and calmly waited until

the lifeless body of her first born son was brought home. There was no loud crying, but a

quiet resignation to the will of God. William was the first person to be buried in Sand

Hill graveyard, for up until this time the neighbors had buried their dead on their own

land.

About the first of September

1827, Mary suffered a "bilious fever." When Joseph sent for Dr. Kiser, it was

the first time a doctor had been summoned to this home. Some of the ladies of the church

in Columbus came on horseback to show their sympathy and provide as much help as they

could. Mrs. Sloan stayed with Mary through the night of September 10, but left early in

the morning to prepare breakfast for her own family. Knowing she was about to die, when

the sun rose on September 11 Mary gave a parting message to each of her children. Then she

died, as Joseph sang the following verse: About the first of September

1827, Mary suffered a "bilious fever." When Joseph sent for Dr. Kiser, it was

the first time a doctor had been summoned to this home. Some of the ladies of the church

in Columbus came on horseback to show their sympathy and provide as much help as they

could. Mrs. Sloan stayed with Mary through the night of September 10, but left early in

the morning to prepare breakfast for her own family. Knowing she was about to die, when

the sun rose on September 11 Mary gave a parting message to each of her children. Then she

died, as Joseph sang the following verse:

Jesus can make a dying bed

Feel soft as downy pillows are;

While upon His breast I lean my head

And breathe my life out sweetly there.

The family began the day with a simple breakfast and worship. The next day Mary was

laid to rest in Sand Hill graveyard by the side of her son William. Without a woman to

care for their household needs, Joseph and his sons felt they could no longer live

together. The two older boys went to live with two families in the neighborhood during the

coming winter. Joseph and his younger son (C. C. Hart himself) went to live with Gideon

Blackburn Hart who had married and was living on a farm one mile northwest of the home

place. And the little cabin where the family had dwelt for six happy years was sold to

strangers.

In March 1828, James Harvey was apprenticed to John B. Abbot of Columbus, Indiana to

learn the tailor’s trade. There he served for six years.

In May 1828, Joseph and his 15-year-old son Samuel traveled to Columbia, Maury County,

Tennessee where Joseph Hart, Jr. was then residing. Joseph bought a one-horse Jersey wagon

to make the trip. The women of the church spun and wove some cloth, and then met at Gideon

Hart’s house to make suits of clothes for Joseph and Samuel. Also, for Joseph, they

made a Scotch plaid coat with a belt and a velvet collar. (This was the most stylish coat

that had ever been seen in the neighborhood!) The trip to Tennessee took two weeks, and it

was the only journey Joseph ever made in a wheeled vehicle. Joseph remained in Tennessee

two years, teaching most of the time he was there, and then he returned to Indiana on

horseback, leaving Samuel behind. He lived with his son Gideon for the rest of his life.

After Joseph returned to Indiana, Congressman William Herod visited him in 1830 to try

to persuade him to apply for a pension as a Revolutionary War veteran. But Joseph said,

"No; I did not go into the army for money, and I served only a short time."

The congressman replied, "But you were wounded in the service and partially

disabled for life."

Joseph answered, "True, but I did very little service for the country. The

government is now in debt, and I cannot ask for money." Nobody ever persuaded Joseph

to apply for the pension, though several tried.

After his return from Tennessee Joseph taught school several summers, either in his own

neighborhood or in the Haw patch. (I do not know what a "Haw patch" is, and C.

C. Hart did not explain. --BA) In February 1836 when C. C. (Charlie) Hart was a lad of

sixteen, Joseph sent him about sixty miles away to Salem, Washington County, Indiana to

learn a trade. In the following May, Joseph went to Salem and apprenticed Charlie to David

T. Weir to learn the cabinet maker’s trade. The papers of indenture were carefully

drawn by Joseph, binding the lad to four years’ faithful service. The papers were

signed by Joseph and Mr. Weir, and then recorded in the office of the recorder of deeds

and indentures. Joseph then returned home.

Some time before this, Joseph’s only daughter Elizabeth and her husband William

Trotter had moved from East Tennessee to Walnut Ridge, Indiana, ten miles north of Salem.

Joseph visited them in the spring of 1837 and taught school in their neighborhood. This

was the last school he ever taught. He spent the fall and winter at home with Gideon, and

then he returned to Walnut Ridge in the spring of 1838 expecting to teach again; but a

suitable schoolhouse could not be procured.

Apparently around this time there was great dissension in the Presbyterian Church. In a

letter written to his sons in Tennessee from Walnut ridge, Joseph expressed great distress

on account of the division of the Presbyterian Church into Old School and New School,

claiming that the division was unnecessary and a violation of the constitution of the

church. He became a staunch New School man, but always was charitable to members of the

opposite party. (Apparently the separation was caused by disagreement over the question of

slavery, with the Old School accepting the practice and the New School opposing it. I

reached this conclusion after reading a comment in Chapter III of Joseph Hart and His

Descendants.--BA)

His return from Salem to Bartholomew County in 1838 was the last journey Joseph made on

horseback, his favorite mode of travel. He spent a considerable part of his time in his

last years working for the American Bible Society.

Joseph Hart stood five feet eight inches in height and he weighed about 130 pounds. He

was always clean and neat. He never had a pair of boots, and he never wore suspenders. He

wore a low hat with a broad brim. His letters, written to his children from 1825 to 1838,

were very lengthy, correct in spelling and grammar, and clear and concise in composition.

Joseph’s handwriting was a marvel too; the paper he used was large and unlined, but

the text was as straight as if written on ruled paper. The letters were well-formed; every

"i" was dotted and every "t" was crossed. Postage for each letter was

25 cents.

In September 1839 Joseph suffered a stroke which left him paralyzed in his right side,

and he never completely recovered. About a year later he had another stroke which left him

almost helpless. After this he never left his room, and for six months before his death he

could not lie down on account of a "dropsical affection." (C. C. Hart

didn’t explain that one either.--BA)

During his final illness, Joseph’s granddaughter, Mary E. Braden of St. Louis,

Missouri served as his faithful attendant during the day. At night his son Gideon was his

nurse. Gideon’s wife Hetty was also most helpful.

C. C. (Charlie) Hart visited his father five weeks before his death. Joseph told

Charlie, "My son, I shall live but a short time. When you hear of my death do not put

on any outward sign of mourning; it will be a time of great joy to me." Joseph died

on the morning of June 20, 1841.

Thomas Hart

In 1901 when C. C. Hart wrote the account above, he said he had knowledge of about six

hundred descendants of Joseph Hart. Now we will follow the story of one of those

descendants: Joseph’s son and C. C. Hart’s half-brother, Thomas.

As previously stated, Thomas Hart, second son of Joseph and Mary Hart, was born in the

Blockhouse at Maryville, East Tennessee on October 26, 1791. He was brought up on a farm

three miles north of his birthplace, with the usual experiences of a boy of that day.

Being a son of Joseph Hart, he had a good example to follow, and good influences about

him. As his father was a teacher, Thomas had good educational opportunities; he was very

fond of reading and he had an excellent memory. He enjoyed conversation, but he was a

modest man and he preferred to listen rather than to speak. He kept his home in Tennessee

for a number of years after his father Joseph and other members of the family moved to

Indiana. He was five feet ten inches tall and weighed 165 pounds.

Thomas became a soldier in the War of 1812. He enlisted in Blount County, Tennessee,

May 31, 1812 in Captain Samuel C. Hopkins’ Company, Second Regiment U.S. Dragoons,

under Colonel James Burns. The command marched to the north and joined the Northwestern

Army, under the command of General William Henry Harrison. In passing through northern

Ohio they frequently marched in water from three to sixteen inches deep, chopped down

timber and bivouacked in the brush. Thomas participated in the siege of Fort Meigs, where

he was wounded in the heel by an Indian concealed in a treetop. Because of this wound, for

the rest of his life he was slightly lame. Thomas was in the battle of River Raisin, and

many other engagements under General Harrison. He remained in the service until January

17, 1814 when he was mustered out at Watertown, New York.

During his life, Thomas witnessed major changes in the United States. While in the army

he walked all the way from Tennessee to Canada through an almost unbroken wilderness. By

the time of his death, this area had grown into a densely populated and thrifty land of

schools, churches, cities, railroads, telegraphs and homes with the comforts and luxuries

he never knew in his youth. This was a neverending source of interest to him, and he often

noted society’s progress and compared the differences between the various periods of

his life.

Early in life Thomas joined the New Providence Presbyterian Church of Maryville, and he

was a faithful Christian. He was greatly distressed by the division of the Presbyterian

Church into the New School and the Old School, but as he was an opponent of slavery he

remained a firm New School man. It was a great joy to him when the Church reunited in

1869.

On December 15, 1814 Thomas married Miss Elizabeth Duncan of Blount County, Tennessee.

Miss Duncan was born in rock Ridge County, Virginia, December 17, 1796. She was a member

of new Providence Church, and a daughter of George Duncan, a well-to-do farmer, a noted

gunsmith of that time, and a mechanical genius generally. He was the son of Scotch parents

who early emigrated to Virginia. He was also a soldier in the Revolutionary War. His wife

died early in life, and his 12-year-old daughter Elizabeth, or Betsy as she was known,

took charge of the house and the youngest children. She performed her duties well, giving

the children all the love and care of a mother, teaching them morals and manners and

giving them religious training. Her father remarried some years later, and the new

stepmother, upon coming into the household, said that she was surprised to see a girl so

young exhibit such capability.

Thomas and Elizabeth Hart were the parents of eleven children; ten daughters and one

son. Their names were Lavina, Nancy, Angeline, Mary Ann, Elizabeth, Eleanor Jane, Benjamin

Franklin, Harriet Newel, Marth L., Frances C, and Frances Juliette. Two of these children

died in early childhood, Frances C. and the only son, Benjamin Franklin.

Something mysterious happened to Thomas and Elizabeth, just a few years after the death

of their only son. One day a strange woman, with a male child about 18 months old, came to

their house and said that as they had daughters and no son, she wished to give them her

child. She would not reveal her own name or that of the child’s father. After some

persuasion and a promise never to come to see the child, Thomas and Elizabeth agreed to

take the little boy and raise him as their own, which they did, and the mother never

returned. The child received all the care and affection of a son, and was known as Jim

Hart. When he came to manhood he married a Miss Blessing in Bartholomew County, Indiana.

He and his wife moved to Carrollton, Missouri, where for several years he worked as a

carpenter. By the year 1900 he had become a farmer.

The home of Thomas and Elizabeth Hart was warm and loving. To people accustomed to the

luxuries of the present day, their lives may seem hard and bare. But their children had

many bright memories of happy childhoods in East Tennessee. Elizabeth taught her daughters

to cook, and she also taught them knitting, spinning, weaving and sewing. Some of the

older girls attended school to learn needlework, writing and singing. They learned to sing

"Hail Columbia," "My Country ‘Tis of Thee," and "The Star

Spangled Banner." They studied the Shorter Catechism and read only good books. They

took advantage of everything they could to acquire education and useful knowledge.

At one time bands of roving Indians were sometimes seen near the family’s home in

East Tennessee, but the Harts were never molested. Once, though, when Thomas and Elizabeth

were away at a weekly meeting, the children left at home were badly frightened by the

sudden appearance of three or four Indians at the front door. The Indians entered and

looked all about the house, but took nothing. They lifted the lid off the pot where the

dinner was cooking, turned the cover down and took a peep at the babe asleep in the

cradle. Then they nodded, grunted, and left--much to the relief of the children.

One serious accident befell Thomas. On his way home from church with his wife one

Sunday, a temperamental colt, which he was riding, became frightened and ran away,

throwing Thomas against a stump. Thomas’ nose was almost completely torn off,

remaining attached to his face by only a shred of flesh. A good surgeon, with God’s

assistance, reattached the nose, and although the injury was noticeable, it was not

disfiguring to a great extent. It did alter Thomas’ voice, though.

In the fall of 1846, Thomas Hart with all his family, three of whom were by then

married, moved to the state of Indiana. The journey, which took five weeks, was pleasant

in the autumn weather. They brought with them both horses and cattle. They settled on

Clifty Creek in Bartholomew County near the home of Thomas’s father Joseph, and both

Thomas and Elizabeth lived here until their deaths. Thomas became an elder in the

Presbyterian Church of both Columbus and Sand Hill, and he held these offices until he

died on July 28, 1865 at the age of seventy-four years.

At this point in his story,

Thomas’s half-brother, C. C. Hart, provides the following note: At this point in his story,

Thomas’s half-brother, C. C. Hart, provides the following note:

About two months before his death I heard he was feeble. I made a journey of 250 miles

to visit him. When I arrived he expressed great pleasure and asked how long I could stay.

"Till tomorrow morning," I replied.

"I want you to preach here this evening, for that will be the last sermon I shall

ever hear." The neighbors came, many of them his children or grandchildren. The

women filled the house and the men on makeshift seats filled the dooryard. I stood in the

door and preached from Peter 1:8. (C. C. Hart didn’t say whether it was First or

Second Peter...BA) After the people had retired, we talked until midnight. He was not

sick, but feeble, cheerful and happy.

For several years Thomas and Elizabeth, being too feeble to live alone, made their home

with their son-in-law, William McDowell. After Thomas died, Elizabeth continued to live

there until she too died on July 7, 1868. They both lie buried in Sand Hill graveyard by

the side of Joseph Hart, brothers and many of their children and grand children.

Nancy Hart McAllie

Nancy, the second child of Thomas and Elizabeth Hart, was born January 22, 1818 in

Blount County, Tennessee. Early in life she became a member of the New Providence

Presbyterian Church. She was educated at the neighborhood school, and was married to David

Eagleton McAllie September 24, 1835. David was a member of the New Providence Church, took

a partial course at Maryville College, and was a farmer and a teacher. Nancy and David

moved to Clark County, Indiana in March 1844, and to Bartholomew County, Indiana in 1851.

Here David engaged in farming and teaching, and for several years he was connected with

the wool carding business at Lowell Mills, Indiana. He died in Newbern, Indiana on

December 14, 1893. Nancy was still living in 1899. She had a long and useful life in which

she won the love an esteem of a host of friends by her constant cheerfulness and

thoughtfulness for others. With the many cares of a large family resting on her, she could

always enter into the joys and sorrows of those about her. In her widowhood she made her

home with her youngest daughter, Mrs. John A. Williams, at Taylorville, Indiana. Nancy and

David were the parents of nine children:

Thomas Franklin, the first child, was

born in Blount County, Tennessee February 27, 1838. He married Miss Jane Frost of Newbern,

Indiana September 1860 and they had 13 children. Thomas Franklin, the first child, was

born in Blount County, Tennessee February 27, 1838. He married Miss Jane Frost of Newbern,

Indiana September 1860 and they had 13 children.

Mary Elizabeth, the second child, was born in Blount County, Tennessee June 23, 1839.

She was married to Mr. Dennis Hopkins, a worthy and prosperous farmer of Bartholomew

County, Indiana, September 25, 1856. They had ten children.

Margaret, the third child, was married to Mr. Henry Ueberroth, a merchant of Columbus,

Indiana, September 28, 1859. They had two children.

Josephine I., the fourth child, was born January 11, 1843. She married Frank F. Wills,

an expert miller of Lowell Mills, Indiana on August 3, 1862. They had seven children.

The fifth child was named Alice J. M. McAllie, and she is the daughter in whom we are

most interested....

Frances Emma C., sixth child of David and Nancy McAllie was born November 16, 1848 and

died in August 1861.

John Calvin, seventh child of David and Nancy McAllie, was born July 7, 1851. He was

married to Miss Elizabeth A. Edwards of Newbern, Indiana on September 28, 1871. They had

ten children. One of them, Harry Waldron McAllie, born January 2, 1876, enlisted in

Company F, U.S. Infantry, in April 1898. C. C. Hart says that Harry, with his regiment,

"was all through the campaign in Cuba; he was at the capture of El Caney; and when

the U.S. Army attacked San Diego, Harry was one of the detail sent forward to cut the

wires, which were such an effectual defense of the city. It seems almost miraculous that

he came through that and many other thrilling adventures without a scratch. He returned to

the United States in August 1898, and was promoted to corporal for his bravery during the

Spanish-American War. In February 1899, he, with his regiment, embarked for the Philippine

Islands for duty." Another son, Ralph McAllie, enlisted as a private in Company K,

16th Indiana Volunteers, July 3, 1898. In August the regiment was ordered south, and in

December to Havana, Cuba.

Samuel Blackburn, the eighth child of David E. and Nancy McAllie, was born July 2, 1854

and died September 22, 1861.

Dora E., ninth child of David and Nancy McAllie, was born April 30, 1858. She married

John A. Williams, a farmer and carpenter of Taylorsville, Indiana on November 22, 1877.

Alice

McAllie Anderson Alice

McAllie Anderson

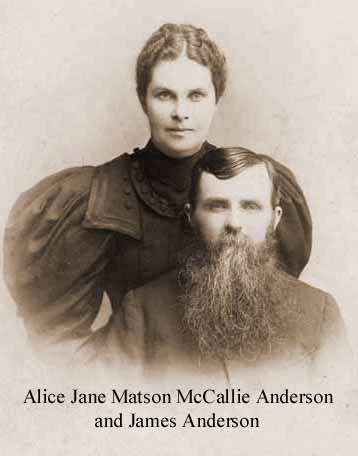

Alice J. M., the fifth child of

David Eagleton and Nancy Hart McAllie, was born at Henryville, Clarke County, Indiana, May

13, 1845. She was a universal favorite among all the relatives for her sweet personality.

She was married at Lowell Mills to James Anderson, a miller, June 14, 1865. They had three

children:

Their first child was Cora Jim, who was born July 7, 1866. She married Mr. Frank Porter

on October 24, 1894, and they had two children: Virginia A. and Harold A.

Their second child was Nancy Kate, who was born on June 29, 1875.

Their third child was Frank Eagleton Anderson, born on January 28, 1878. In 1901 at the

time of publication of Joseph Hart and His Descendants, Frank was a medical student

at the University of Tennessee.

Now here’s a note for anyone who has read this far. Today is February 29, 1996.

Frank Anderson was my grandfather and I know several anecdotes about his life, and the

lives of his wife and children and grandchildren and even great-grandchildren. One of

those children, Frederick Porter Anderson, is my father. I intend to add more to this

document and include stories about myself and all my cousins, but for the present I will

present just the most basic facts. --BA

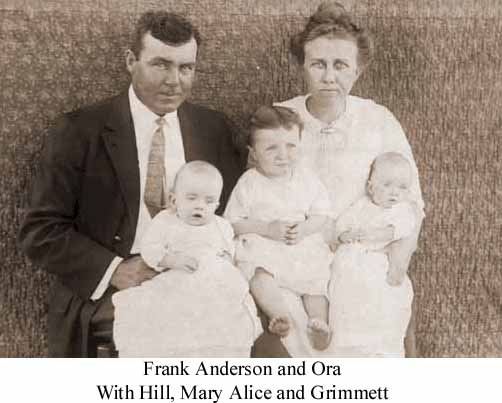

Frank Eagleton Anderson married Savannah Ora Hill December 5, 1912. They had

four children: Mary Alice, born August 29, 1913, and now living in North Carolina, married

Maurice Chauncey Stone and they had two children: James and Mariam Ann; Frank Hill and

James Grimmett (twins) were born November 1, 1914. Grimmett suffered from epilepsy and

fell from his bicycle and died at the age of 15 in 1929. Hill married Tempie Finn in 1937

and they had one son, Douglas Hill, born in 1946. Frank Hill died February 5, 1977. The

fourth child, Frederick Porter (not pictured), now lives in Memphis, Tennessee. Frank E.

Anderson died and was buried in Memphis February 17, 1953. His wife Ora died and was

buried in Memphis July 9, 1959.

Frederick Porter Anderson

Freddie served aboard the U.S.S. Santa Fe in the United States Marine Corps, Pacific

Theater, in World War II. He married Leta Fay Thompson on August 11, 1945 in Brunswick,

Georgia. After the war, he returned to Memphis, Tennessee and worked as a tire builder for

the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company. He and Leta Fay now live in Memphis. They have two

children: William Earl (that’s me!) and Cynthia Fay.

Cynthia Fay Anderson Jones

My sister Cindy was born March 4, 1950. She married Harry Alex Jones March 19, 1971 in

Memphis, Tennessee, and they now live in Laramie, Wyoming. They have three children: Eric

Anderson, born October 20, 1979; and Laura Hill and Elizabeth Ora (twins) born February

29, 1984. (Yes, the day I am writing this is the day Laura and Elizabeth become 12 years

old on their "third" birthday, as they were born on "Leap Day.") The

man named Mr. Hart who emigrated from Wales to the New World in 1735 was their great,

great, great, great, great, great, great grandfather!

|