|

Today the Road Scholars explored the ruins of an ancient Roman city, enjoyed the experience of passing through customs between two countries that don’t like each other very much, ate entirely too much of a fantastic lunch, and explored the ruins of another ancient Roman city

Another lovely day begins. What is it with the weather in Israel?

Yuk. We need some music to cheer us up.

Since we're really pretty close as the crow flies, how about Elvis singing "Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho?" Yeah, that oughta do it.

We have arrived at the archaeological excavation site of a very wet Bet She’an. Never heard of it? I hadn’t either, until today. And now I just want to know more about it. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beit_She%27an

Beit She'an, also known as Beisan, and historically known as Scythopolis is a city in the Northern District of Israel, which has played an important role in history due to its geographical location at the junction of the Jordan River Valley and the Jezreel Valley. In the Biblical account of the battle of the Israelites against the Philistines on Mount Gilboa, the bodies of King Saul and three of his sons were hung on the walls of Beit She'an (1 Samuel 31:10-12). In Roman times, Beit She'an was the leading city of the Decapolis, a league of pagan cities. In modern times, Beit She'an serves as a regional centre for the settlements in the Beit She'an Valley.

Shari explains it all.

Ignore all the ruins. See that big hill back there? That is the most fascinating part of the picture. That is Tell Beit She’an, a place where people have lived for millennia, building communities of homes and shops and experiencing destruction and starting over and building on top of everything again and again and again until you have that hill, called a “tell.” https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tell_(archaeology) archaeologists explore tells by digging a trench from top to bottom and examining the artifacts they find in it. Basically, they take a plug out of it. I read James Michener’s THE SOURCE a long time ago and enjoyed it immensely. Each chapter of the book tells a story based on artifacts discovered in various levels of a fictional tell. The history of Beit She'an dates back to prehistory. In 1933, archaeologist G.M. FitzGerald, under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania Museum, carried out a "deep cut" on Tell el-Hisn ("castle hill"), the large tell, or mound, of Beth She'an, in order to determine the earliest occupation of the site. The results suggest that settlement of Beit She'an began in the Late Neolithic or Early Chalcolithic periods (sixth to fifth millennia BCE.) Occupation continued intermittently throughout the Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods, with a likely gap during the Late Chalcolithic period. Settlement seems to have resumed at the beginning of the Early Bronze Age I (3200–3000) and continued throughout this period, then went missing during Early Bronze Age II, and then resumed in the Early Bronze Age III. A large cemetery on the northern mound was in use from the Bronze Age to Byzantine times. Canaanite graves dating from 2000 to 1600 BCE were discovered there in 1926.

OK, I concede I'm copying entirely too much from Wikipedia to describe this place. But the more I read about it the more fascinated I became. I'd never heard of Beit She'an and now I've found it's one of the most fascinating locales on the planet. So skip over this if you wish, or if you're like me, read it and be amazed. After the Egyptian conquest of Beit She'an by Pharaoh Thutmose III in the 15th century BCE, as recorded in an inscription at Karnak, the small town on the summit of the mound became the center of the Egyptian administration of the region. According to the Hebrew Bible, around 1000 BC the town became part of the larger Israelite kingdom. 1 Kings 4:12 refers to Beit She'an as part of the kingdom of Solomon, though the historical accuracy of this list is debated. An Iron Age I (1200-1000 BC) Canaanite city was constructed on the site of the Egyptian center shortly after its destruction. According to the Hebrew Bible, around 1100 BCE during a battle against King Saul at nearby Mount Gilboa in 1004 BC, the Philistines prevailed and Saul together with three of his sons, Jonathan, Abinadab and Malchishua, died in battle (1 Samuel 31; 1 Chronicles 10). 1 Samuel 31:10 states that "the victorious Philistines hung the body of King Saul on the walls of Beit She'an". No archeological evidence was found of Philistines occupation, but it is possible the force only passed there. The Hellenistic period saw the reoccupation of the site of Beit She'an under the new name "Scythopolis,” possibly named after the Scythian mercenaries who settled there as veterans. Little is known about the Hellenistic city, but during the 3rd century BCE a large temple was constructed on the tell. It is unknown which deity was worshipped there, but the temple continued to be used during Roman times. Graves dating from the Hellenistic period are simple, singular rock-cut tombs. From 301 to 198 BCE the area was under the control of the Ptolemies, and Beit She'an is mentioned in 3rd–2nd century BCE written sources describing the Syrian Wars between the Ptolemid and Seleucid dynasties. In 198 BCE the Seleucids finally conquered the region. In 63 BCE, Pompey made Judea a part of the Roman empire. Beit She'an was refounded and rebuilt by Gabinius. The town center shifted from the summit of the mound, or tell, to its slopes. Scythopolis prospered and became the leading city of the Decapolis, the only one west of the Jordan River. The city flourished under the "Pax Romana", as evidenced by high-level urban planning and extensive construction, including the best preserved Roman theatre of ancient Samaria, as well as a hippodrome, a cardo and other trademarks of the Roman influence. Beit She'an is said to have sided with the Romans during the Jewish uprising of 66 CE. Copious archaeological remains were found dating to the Byzantine period (330–636 CE) and were excavated by the University of Pennsylvania Museum from 1921–23. A rotunda church was constructed on top of the Tell and the entire city was enclosed in a wall. Textual sources mention several other churches in the town. Beit She'an was primarily Christian, as attested to by the large number of churches, but evidence of Jewish habitation and a Samaritan synagogue indicate established communities of these minorities. The pagan temple in the city centre was destroyed, but the nymphaeum and Roman baths were restored. Many of the buildings of Scythopolis were damaged in the Galilee earthquake of 363, and in 409 it became the capital of the northern district, Palaestina Secunda. In 634, Byzantine forces were defeated by the Muslim army of Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab and the city reverted to its Semitic name, being named Baysan in Arabic. The day of victory came to be known in Arabic as Yawm Baysan or "the day of Baysan." The city was not damaged and the newly arrived Muslims lived together with its Christian population until the 8th century, but the city declined during this period. Structures were built in the streets themselves, narrowing them to mere alleyways, and makeshift shops were opened among the colonnades. The city reached a low point by the 8th century, witnessed by the removal of marble for producing lime, the blocking off of the main street, and the conversion of a main plaza into a cemetery. On January 18, 749, Umayyad Baysan was completely devastated by a catastrophic earthquake. A few residential neighborhoods grew up on the ruins, probably established by the survivors, but the city never recovered its magnificence. The city center moved to the southern hill where later the Crusaders built their castle. In the Crusader period, the Lordship of Bessan was occupied by Tancred in 1099; it was never part of the Principality of Galilee, despite its location, but became a royal domain of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1101, probably until around 1120. According to the Lignages d'Outremer, the first Crusader lord of Bessan once it became part of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was Adam, a younger son of Robert III de Béthune, peer of Flanders and head of the House of Bethune. His descendants were known by the family name de Bessan. Under Mamluk rule, Beit She'an was the principal town in the district of Damascus and a relay station for the postal service between Damascus and Cairo. It was also the capital of sugar cane processing for the region. Jisr al-Maqtu'a, "the truncated/cut-off bridge", a bridge consisting of a single arch spanning 25 feet and hung 50 feet above a stream, was built during that period. Then came the Ottomans, and during this period the inhabitants of Beit She'an were mainly Muslim. There were however some Jews. For example, the 14th century topographer Ishtori Haparchi settled there and completed his work Kaftor Vaferach in 1322, the first Hebrew book on the geography of Palestine. During the 400 years of Ottoman rule, Baysan lost its regional importance. The Swiss–German traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt described Beisan in 1812 as "a village with 70 to 80 houses, whose residents are in a miserable state." In the early 1900s, though still a small and obscure village, Beisan was known for its plentiful water supply, fertile soil, and its production of olives, grapes, figs, almonds, apricots, and apples. Then came the British Mandate period when the city became the center of the District of Baysan. According to a census conducted in 1922 by the British Mandate authorities, Beit She'an (Baisan) had a population of 1,941, consisting of 1,687 Muslims, 41 Jews and 213 Christians. In 1934, Lawrence of Arabia noted that "Bisan is now a purely Arab village," where "very fine views of the river can be had from the housetops." He further noted that "many nomad and Bedouin encampments, distinguished by their black tents, were scattered about the riverine plain, their flocks and herds grazing round them." The 1947 UN Partition Plan allocated Beisan and most of its district to the proposed Jewish state. Beisan, then an Arab village, fell to the Jewish militias three days before the end of the Mandate. After Israel's Declaration of Independence in May 1948, during intense shelling by Syrian border units, followed by the recapture of the valley by the Haganah, the Arab inhabitants of Beit She'an fled across the Jordan River. The property and buildings abandoned after the conflict were then held by the State of Israel. Most Arab Christians relocated to Nazareth. A ma'abarah (refugee camp) inhabited mainly by North African Jewish refugees was erected in Beit She'an, and it later became a development town. From 1969, Beit She'an was a target for Katyusha rockets and mortar attacks from Jordan. In the 1974 Beit She'an attack, militants of the Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, took over an apartment building and murdered a family of four. In 1999, Beit She'an was incorporated as a city.

OK, now you can look at the ruins of Bet She’an. These are Roman, but this city situated right beside the tell dates back further than that. According to the Old Testament, around 1100 BCE during a battle against King Saul at nearby Mount Gilboa in 1004 BC, the Philistines prevailed and Saul together with three of his sons, Jonathan, Abinadab and Malchishua, died in battle (1 Samuel 31; 1 Chronicles 10). 1 Samuel 31:10 states that "the victorious Philistines hung the body of King Saul on the walls of Beit She'an".

Looks very Roman.

Let’s think about more pleasant things, like the lovely mosaic tile floors that still exist in various places around the ruins.

Lots of tiled floors.

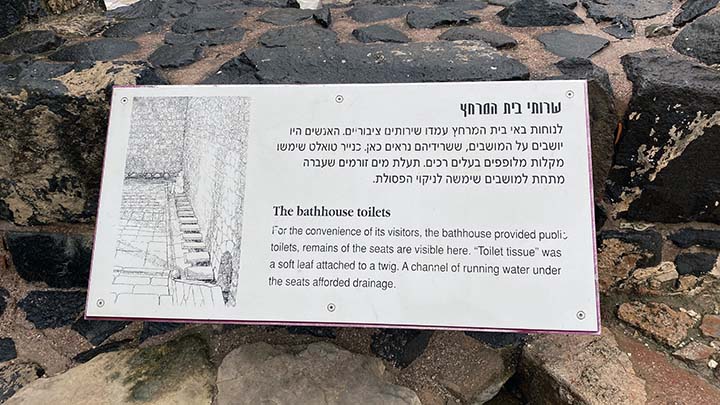

If this is a Roman city, of course there is a bath. These posters describe how it worked. Note that we are in Israel where writing runs right to left. So you need to begin reading these posters on the right side and work your way back.

This is what is left of a dry sauna. Those stone posts are floor supports, and of course the wooden floor is gone. Hot air circulated throughout the posts, heating the floor and the bathers above.

With all this rain there's almost enough water here to take a bath today.

The tourist is cold. He could use a hot sauna about now.

This is the public toilet.

This is how a public toilet worked.

Nice mosaics.

It's a shame, really, how the Nazis brought disgrace to the ancient design of the swastika.

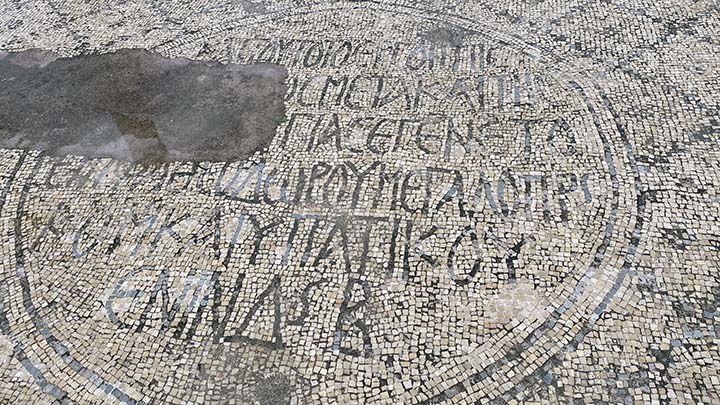

That’s a pretty elaborate mosaic. Can you translate it? Not me.

This one either.

Now we're on our way to Jordan, but no border crossing around here would be complete without annoying procedures.

So let’s say goodbye to Israel and cross over into Jordan. I kinda got the shivers writing that.

Just so you know where you are at all times.

And that my friends is the best glimpse I have had of the Jordan River on the whole trip. Deep River? I don’t think so. Michael, row the boat ashore? Why bother? The boat will hardly fit between the two banks.

We get our papers stamped.

We wait in the rain.

We admire the officialdom.

The tourist is doing just fine. Leave him alone.

Jordan is right through there. We think.

OK, our first exposure to Jordan. Nice.

Not too many people about on a miserable day.

Is the sky clearing? Maybe?

The locals observe the tourists passing by.

We're going up.

The rain is slacking off.

Blue sky! It's a miracle!

Now let's have a Jordanian lunch.

Mmmm, fresh pita bread.

These guys have done this before.

Duck! But no problem. It landed right on the pile where he'd tossed the others.

This is going to be a feast.

But what is it?

Part of the fun is the suspense -- what have they put under there?

Lunch was absolutely delicious, even though I wasn’t exactly sure what I was eating. Except for the French fries. I knew what the French fries were.

Jarrah (aka Gerasa, Gerash or Gerasha) is the capital and the largest city of the Jerash Governorate in Jordan, but in ancient times it was one of the wealthiest and most cosmopolitan cities in the ancient Near East. Settled by humans as early as the Neolithic period (c. 7500-5500 BCE) and founded as a Hellenistic city in the 2nd century BCE, Jerash is today noted for its fine Roman and Byzantine ruins, which rank among the largest and best preserved in the world. Jerash is located 48 km (30 miles) north of Amman - the capital of Jordan - and 40 km (25 miles) south of Irbid, Jordan. Jerash is one of the most visited sites in Jordan after the Nabataean city of Petra.

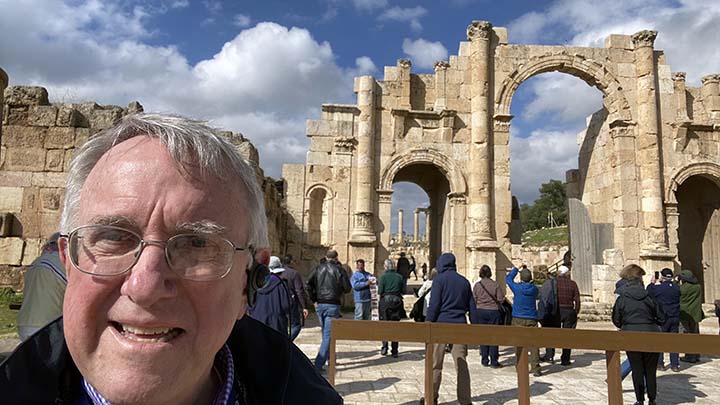

The Roman Emperor Hadrian (117-138 CE) stayed in Jerash during the winter of 129 CE, and this extended sojourn was celebrated with the construction of a triumphal arch that is known as "Hadrian's Arch."

The tourist always enjoys seeing ancient arches.

Beneath the foundations of a Byzantine church that was built in Jerash in AD 530 there was discovered a mosaic floor with ancient Greek and Hebrew-Aramaic inscriptions. The presence of the Hebrew-Aramaic script has led scholars to think that the place was formerly a synagogue, before being converted into a church.

Jerash has a well preserved hippodrome, or Roman circus. Built for chariot racing it is the smallest known hippodrome of the Roman Empire. The monument was probably completed in the early 3rd century and it could accommodate up to 17,000 spectators.

Let's go in and see it.

Crowds of up to 17,000? For chariot races?

Yeah, well it's big enough.

These were the starting gates.

And those were the seats.

That's the Jerash Nymphaeum, A nymphaeum or nymphaion, in ancient Greece and Rome, was a monument consecrated to the nymphs, especially those of springs. These monuments were originally natural grottoes, which tradition assigned as habitations to the local nymphs. They were sometimes so arranged as to furnish a supply of water.

Maybe we can get a better view over here.

It was basically a public fountain.

The tourist is loving this.

What's that down there?

Oh, an olive oil press.

Jerash is considered one of the largest and most well-preserved sites of Roman architecture in the world outside Italy.[10] And is sometimes misleadingly referred to as the "Pompeii of the Middle East" or of Asia, referring to its size, extent of excavation and level of preservation.

It is definitely well preserved. The Oval Forum is a magnificent public plaza paved in limestone and surrounded with Ionic columns.

OK, Jerash is comparatively well preserved.

The cities of the Ancient Roman Empire had a special tradition of decorating main roads with spectacular stone columns. These streets were called “Cardo.”

More Nymphaeum.

And over this way...

Is a magnificent amphitheater.

Supposedly there is a spot from which a speaker can be heard from anywhere in the stands.

Our new Jordanian guide is called Mo.

But Shari is still with us, acting as group organizer while Mo attends to entertaining us with facts and interesting stories.

Of course the tourist climbed to the top of the amphitheater. He wasn't going to miss any part of this adventure.

Provide a stage and everybody wants to perform.

The tourist is tired but happy.

The Cardo Maximus was a grand colonnaded street that ran 800 meters through the city, bearing witness to a once flourishing civilization. The imposing columns were ornate Corinthian style and the Agora (shops) lined both sides of the wide street. Incredibly, a 2,000-year-old underground sewage system ran beneath the street and drained rainwater from the surface. Deep grooves worn into the ancient cobblestones attest to hundreds of years of chariot and wagon traffic.

So let's stroll the cardo with the ghosts of all those old Romans.

Imagine shops all around.

And careful not to get your feet caught in the pavement.

All this and as we are leaving, a call to prayer.

Amman traffic.

Our hotel for the evening. Very nice. Road Scholar really looks out for us.

Over there to the left behind those buildings is a genuine Starbucks. That's where I bought my only souvenir coffee cup of the trip. I would have liked one from Jerusalem and one from Cairo, but no Starbucks to be found there. Amman? No problem.

|